Wadsworth turned 209 on March 1, 2023 and we thought you’d enjoy this article by the wonderful Caesar Carrino in the Wadsworth Area Historical Society newsletter, (Vol. 9, Issue 3)

Wadsworth turned 209 on March 1, 2023 and we thought you’d enjoy this article by the wonderful Caesar Carrino in the Wadsworth Area Historical Society newsletter, (Vol. 9, Issue 3)

TWO-HUNDRED PLUS NINE

By Caesar Carrino

As we start the 209th anniversary of the founding of Wadsworth – March 1, 1814 – we continue to find historical facts about the people who were responsible for what we are enjoying today. There are several books on the history of

Wadsworth and probably more will be written in the future. What we don’t have are the detailed accounts of the person after whom Wadsworth was named, General Elijah Wadsworth. We know the reason Wadsworth got its name

from Elijah is that he contributed more money for the area we call Wadsworth than the other five who contributed with him. We also know that he never lived in Wadsworth and, in fact, never came to Wadsworth that anyone can prove.

We knew he fought in the Revolutionary War and in the War of 1812. We know he lived in Canfield and was the first Postmaster there. We also know that he was born in Connecticut. We don’t know, however, some of the less dramatic

episodes of his life that produced the person whose name identifies our City. Elijah was born on November 17, 1747, in Milton MA. He died December 30, 1817. His father was Samuel Wadsworth. His mother was Anne Withington. Elijah’s siblings were: Nathaniel [1721, died at birth], Hephzibah [female] [1728-1790] and Ruth, [1734-1792].

Long before Elijah became a name in this section of the Connecticut Western Reserve, the Wadsworth name was famous in Connecticut and around New England in general. William Wadsworth and Thomas Hooker founded Hartford, Connecticut. His brother, John was associated with Harvard University and is buried on the grounds there. Peleg, another brother of William, was the grandfather of poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Elijah’s great-grandfather was Captain Joseph Wadsworth, of Charter Oak fame. Joseph picked up the original Connecticut Charter at the open window from the colonial leaders who were waiting for the English authorities who were coming to take the Charter away from Connecticut. Joseph rode it to a nearby oak tree and hid it in the crotch of that tree. Joseph’s action saved Connecticut from being returned to England. The Council gave the English officials an exact copy of the charter, so the original charter was still extant – in the crotch of the oak tree. The tree became known thereafter as the Charter Oak. It was blown over

on August 21, 1856 by a violent storm. It is estimated the tree was 1000 years old when it was felled by the storm. A monument stands in its stead.

Elijah was not always in the limelight of greatness: Despite his family being endowed with much money, he chose to be a blacksmith. He was also a Civil Engineer. Having a trade was probably a cultural necessity, since nearly every person who came from the East had a trade. While pounding out heated pieces of iron to make a tool or a trinket, his mind wandered to greater horizons, such as becoming one of the first principals in the Connecticut Land Company, the Company that owned the Connecticut Western Reserve, where we live. He also recognized that, while almost all of his people in New England came from England, there were other people who settled in other parts of the ‘new’ territory that would later become the United States. These people were Germanic and settled in what is now Pennsylvania. Despite cultural differences, Elijah energized the mail route between Pittsburgh and the Northeast.

In 1796, Elijah came to the Connecticut Western Reserve to help survey land. He took up residence in the village of Warren, but then moved his family to Canfield, a desolate land that he could build from its roots. He became the first postmaster, then Sheriff, helped organize the local government, helped to establish schools in the area and helped build roads where necessary.

Just as he had done in the Revolutionary War a few years earlier — he served under the direct command of General George Washington — he volunteered to fight the English once again. He was assigned as the Major General of the Fourth Division, which included the northern part of Ohio in the War of 1812. There are documentations that Elijah, although of English ancestry himself, was so opposed to the tyranny with which the English were meting out to the colonists, that he elected to fight them in both wars. During this last venture in the War of 1812, he became stricken with paralysis and died on December 30, 1817. Although there is no proof of what afflicted him, it is generally considered he was paralyzed by a stroke, although documents indicate he had palsy.

Elijah married Rhoda Hopkins on February 16, 1780, at age thirty-three. They had four children, Rhoda Wadsworth Clark [1784-1830] who died at age forty-six; Frederick [1786-1869] who died at age eighty-three; Edward [1791-1835] who died at age forty-four; and George [1793-1832] who died at age thirty-nine. Although these were young ages for people to die – except for Frederick — it was not necessarily uncommon. The house in which Elijah had built in Litchfield CT was later purchased by Dr. Lyman Beecher, father of Henry Ward Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe, both famous for their

contributions to literature studied by nearly every student in the United States.

Elijah was an avowed Mason and established Masonic Temples everywhere he went. He named all the Temples Western Star. The Masonic Temple in Youngstown OH still stands and is the last one in this area to be named Western Star. Although there is evidence that the Western Star that is close to Wadsworth was named by a person whose name was Starr, there is also the possibility it was named Western Star because of the proliferation of Western Stars Elijah created as Masonic units.

After Elijah’s death, his son, Frederick, became an avowed activist against Free-Masonry, probably because of the groundswell of outrage migrating throughout the colonies with the murder of William Morgan. Morgan was a former Mason who became a fierce critic of Masonry and was murdered, ostensibly by Masons, but who were not prosecuted because they were protected by other powerful Masons. Frederick became so adamant about his distaste for Free Masonry that he actually attended the Anti-Masonic Party Convention in Philadelphia to help choose a Presidential candidate to oppose

anyone from any other party who was a Mason.

Frederick became Mayor of Akron in 1852 and served through 1853. The Anti-Masonic movement had died by this time with most of the proponents joining the Whig Party. It is not known whether Frederick was still affiliated with the Anti-Masonry movement as Mayor, or whether he relaxed his activism when the Anti-Masonry impetus waned a few years earlier.

There is a touching story about Elijah that makes his aggressive and charging-forward behavior appear as that of a mendicant child: When Elijah became Commander of the northern part of Ohio, he had little money, despite coming from wealth. There is no indication that he asked his family for money, or whether the logistics of receiving money from them in a timely manner would have been soon enough, given the distance involved – six-hundred miles, three months travel. With a humble gesture, he went to the headquarters of his command, and with a plaintiff voice and cap in hand,

announced that he did not have a penny left, and asked if they would give him some so he could eat and feed his family. This man of previous wealth had never had to do this before, but desperation transformed his prideful heart into a basic self-preservation necessity. He begged for the first time in his life. Shortly after all his ventures of military, local and state greatness, he ‘became stricken’ and paralyzed. He was confined to his home in Canfield with his family providing care, especially his wife. Then he died at age seventy.

There is evidence that the Wadsworth family still walks the roads of England. About twenty years ago, the then Wadsworth Mayor received a long letter from Paul Wadsworth, whose great-great-great-grandfather was Elijah Wadsworth. Paul was in his eighties at the time and wanted to come to Wadsworth OH to visit the only Wadsworth that was named after his ancestor, Elijah. There are other Wadsworths in other states, but our Wadsworth is the only one named for Elijah. The Mayor welcomed the thought of Elijah’s ancestor coming to Wadsworth, but, after some mutual

correspondence, learned that Paul would not be able to afford the trip and that his health was somewhat precarious.

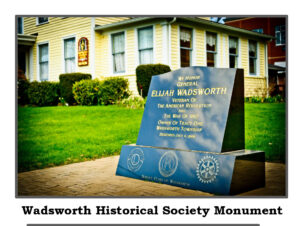

Elijah is buried in the Canfield cemetery, on the north side of Route 224 in Canfield OH. His original stone was approximately five feet high, two feet wide and eight inches thick, with all his accomplishments etched into the stone. Approximately forty years ago, the stone was replaced by a more modern stone, smaller in size, but with cogent facts about his life that people can read. The etching in the old stone had worn away to the point that it was almost illegible. Wadsworth has a stone honoring General Wadsworth as well, inscribed with his service in the Revolutionary War and

the War of 1812. The Lions, Kiwanians and Rotarians donated the stone. Despite all he did for Ohio – including naming our town – his stone is placed above his grave in an inauspicious manner. Across the highway, a little ways down the street, stands the first frame house that was built in Ohio, built by Elijah Wadsworth. The house bears his spirit; the grave, a short distance away, conceals his spirit.

Wadsworth continues to live and prosper here in the Connecticut Western Reserve and on the streets of England as well. It fulfils the Latin saying, loosely translated: Natum est; vivat in vita aeternam. He is born; let him live the endless life. Wadsworth was born 209 years ago: let it live the endless life.